This post is dedicated to Ivan Towlson. Ivan taught me FParsec; and has both put up with, and instigated, a stream of incorrigble puns every time we converse. Thanks, Ivan! It’s been a genuine pleasure working with you!

Introduction

The Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP) is one of the most widely studied NP-complete problems. There are many heuristic solutions in the industry and even a regular competition to evaluate the performance and efficiency of heuristic solutions.

The canonical source of problem sets is available from the University of Heidelberg. There are several datasets and multiple variants of the problem represented here.

This post will discuss the development of a Parser to be able to read and process the problem set data, so that we can then work with known data and potentially compare our performance and correctness with known results.

Problem Structure

The TSP can be thought of as a graph traversal problem. Specifically, given a positively weighted graph, solving the TSP is equivalent to finding a Hamiltonian Cycle in that graph.

Practically, one usually encounters a complete graph (i.e one where every node is connected to every other node), and generally speaking, one is presented with a symmetric graph where the distance from A to B is the same as the distance between B and A.

At the outset, one might feel uncomfortable that this set of constraints doesn’t represent reality - after all, one-way roads do exist, and generally a real city is only directly connected to a few other cities. We will note this discomfort and model the problem in such a way that the more general solution for incomplete, asymmetric graphs is also addressed by our solution.

Consequently, to represent the problem, one must first constructed a weighted graph, where the nodes represent cities and the weights of the edges represent the distance between them. If one implements this graph as an adjacency matrix, we can immediately see that we can represent disconnected cities (cities without a direct connection between them) as having an edge with infinite weight; and asymmetric edge weights are easily supported by storing data in a full matrix with different distances in each direction.

If one numbers the nodes, then a TSP tour would be some sequence of numbers representing the cities in the order of traversal. That is, a permutation of the sequence 1, 2, 3, ... n would represent a tour of the set of cities.

It is then easy to compute the total distance of the tour by summing together successive distances. For example, a sequence of 5, 3, 4, 2, 1 would have a total tour distance of the sum of distances between 5 and 3, 3 and 4, 4 and 2, 2 and 1, and 1 and 5. If there were no connection between 4 and 2, that edge would have infinite weight, and the tour would have infinite distance - indicating that this sequence does not constitute a valid tour of the five cities.

A typical data structure for this might be:

type WeightedCompleteGraph (dimension : Dimension) = class

let d = dimension.unapply

let mutable fullMatrix : Weight[,] = Array2D.init d d (fun _ _ -> Weight.Infinity)

end

Note that we have elided support types such as Dimension and Weight here, and have made the array mutable because we may have to do significant computing before we populate the array with weights.

Input Data

We now turn our attention to the structure of the input data specified in the TSPLib repository. Whilst there are several libraries on Github that purport to read problem instances from the TSPLib repository, one realises that they are largely focussed on one particular variant of the problem.

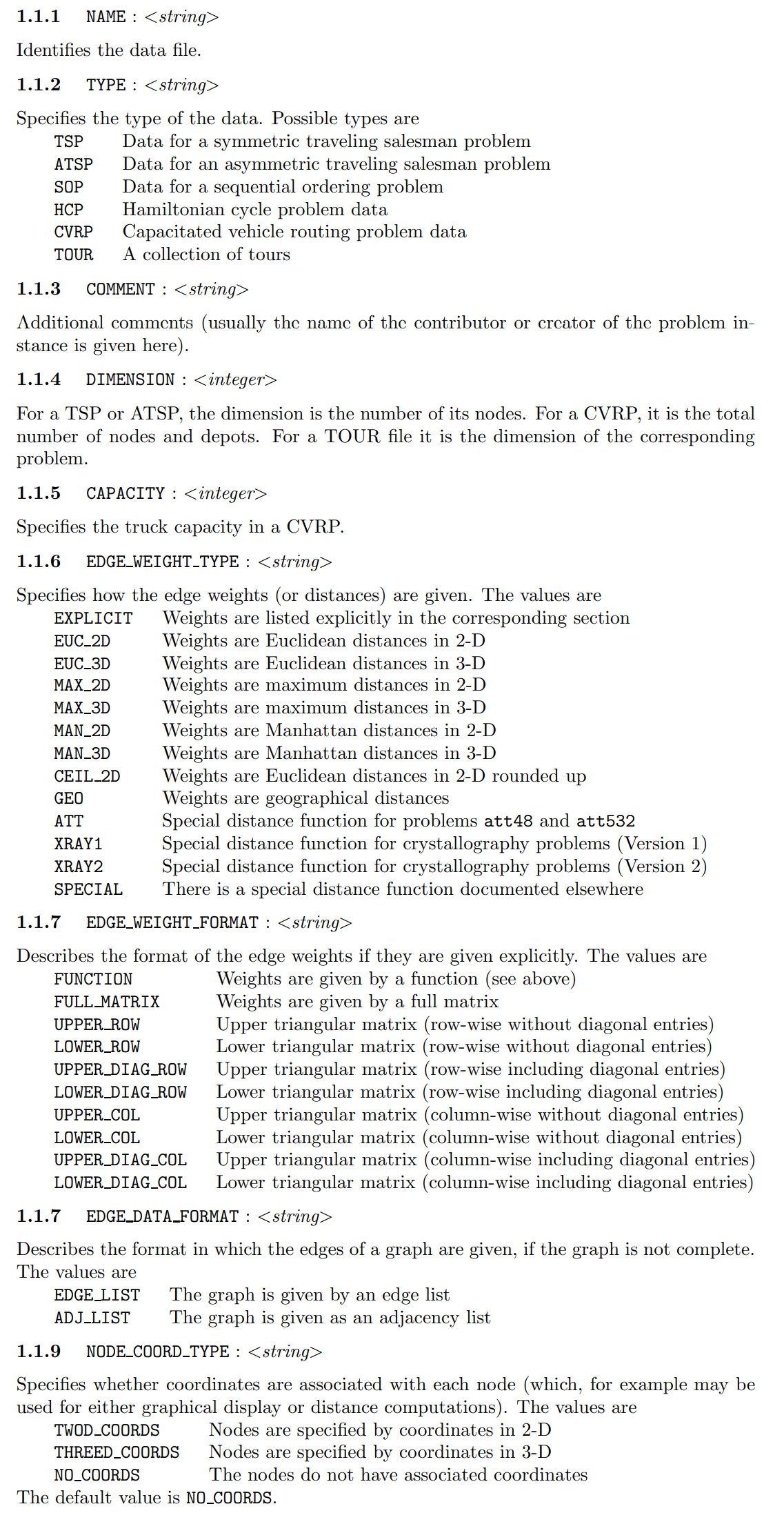

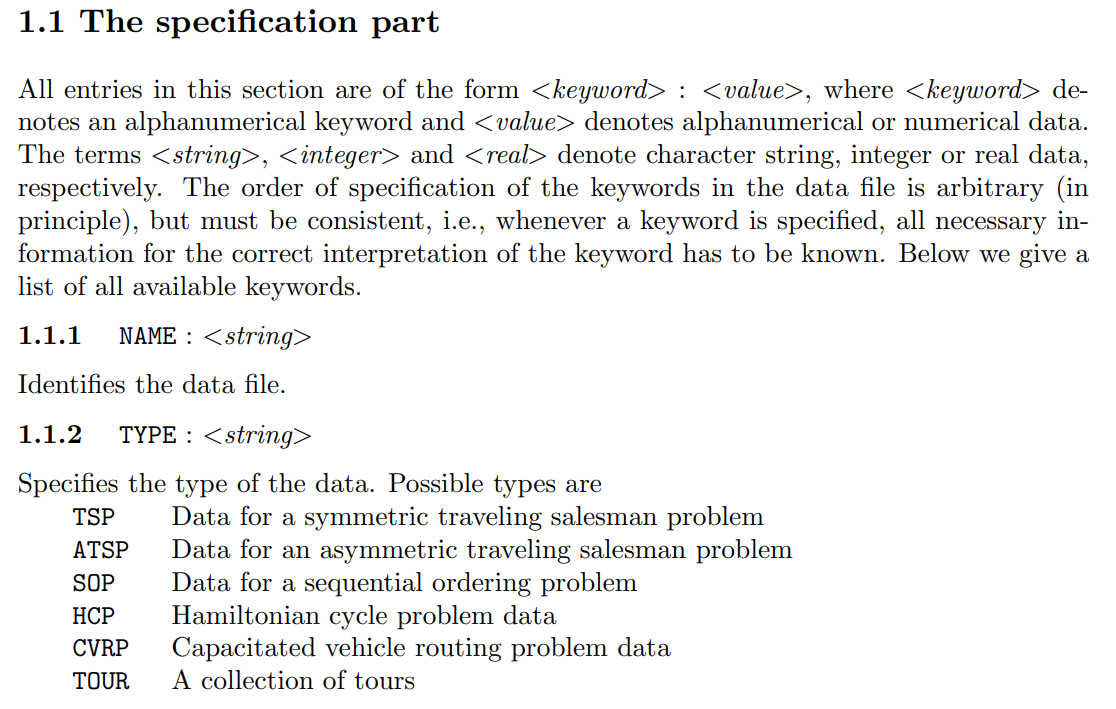

In contrast, the documentation comprehensively describes a wide variety of data formats encoded in the files. A given TSP data file can describe six varieties of data; edge weights as one of thirteen types, edge weight data in one of ten block formats, and nodes as having two, three, or no coordinates with nine possible distance calculation formulae if the distances aren’t specified explicitly!

A functional programmer would immediately recognize the documentation as an informally specified domain-specific-language (DSL), and recognize each data file as a document conforming to the DSL. This naturally implies that in order to read in the data and make sense of it, one must develop a parser which can build a data structure containing the data consumed and transformed.

In this post, I’ll walk you through how to build a simple parser in FParsec.

Writing A Parser

We will be writing a parser using a “parser combinator” library called FParsec. You can think of a parser as a kind of function that recognizes a text pattern, and a parser combinator as a function that glues two or more parsers into a parser that recognizes bigger patterns.

As we start writing parsers, we also want data structures to store the information we’ve parsed - the patterns recognized - so we can transform the textual input of a parser into structured data. In F#, we have sum and product types (or union and record types) to define the data structure type, and we will basically transform textual input into an instance of one of our types - or die trying!

This data structure is traditionally called the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), because one of the common uses of a parser is to parse the text of a program into something that conforms to a language syntax before being processed semantically.

We’ll walk through the development of parsers for some of the basic patterns of data, and you can peruse the complete source code, examples, more examples, or the documentation for further information.

Converting Specifications To Data

The Specifications section of the TSPLib documentation starts with:

From this, and from reading the rest of the document, we note a few things:

- The section headers are of the form

<keyword> : <value> - The

<value>portion is typed, and can bestring,integerorreal - Keywords can appear in any order

- Some values are constrained to be one of an enumeration, such as the “Type” keyword

- Some keywords are optional, and if not provided, may have default values

- Semantically, if some keywords are specified, others maybe required or precluded

The last two points are worthy of note, because we will have to address them in the semantic verification stage. It will not be apparent at the syntax parsing stage if these are satisfied.

AST Types

Let’s start with a parser for the “Name” section as it is the simplest.

When we parse this section, we will need to store the provided string value as the Name property in our data structure, so define a Name type for the AST:

type Name = | Name of string

with

static member inline apply = Name

member inline this.unapply = match this with | Name x -> x

The apply and unapply functions may look a little strange, but they are there for a reason - we will find them useful when we use a parser which extracts multiple values from a pattern.

Parser Structure

Then we write the Name parser. We basically need to successfully parse the following pattern:

- (whitespace)NAME(whitespace):(whitespace)<value>(whitespace-except-end-of-line)(end-of-line)

The NAME and : are literal patterns which we need to match, but which don’t have any real other importance. The <value> bit is the string we need to capture.

Dealing with spaces and end-of-line separately

The tricky bit is that the built-in spaces parser will greedily process the end-of-line as well, so we need to use a different way of knowing when we’re at the end of the line.

The following spacesExceptNewline parser skips as many tab characters or spaces and just ignores them.

let spacesExceptNewline : Parser<unit, unit> =

(skipChar '\t' <|> skipChar ' ') |> many |>> ignore

Combining Parsers

We don’t get very far with the built-in set of primitive parsers. The power of parser combinators comes from being able to compose more and more complex parsers with combinators, to being able to parse more and more complex patterns.

The ws_x_nl parser combines a given parser p with the spacesExceptNewline parser on either side, and preserves the output of the p parser. The ws parser does the same, wrapping p with parsers that snarf all whitespace from either side of it.

let ws_x_nl p = spacesExceptNewline >>. p .>> spacesExceptNewline

let ws p = spaces >>. p .>> spaces

The >>. combinator combines two parsers and keeps the output of the right parser (the . is to the right of the >>); The .>> combinator combines two parsers and keeps the output of the left one. The key is to see where the . shows up in the combinator. When we encounter the .>>., we’ll see the usefulness of the .apply pattern mentioned above.

Once we write the parser and refactor out the reusable bits, we can write the specificationName parser as:

let tillEndOfLine : Parser<string, unit> =

manyCharsTill anyChar newline

let parseSpecification prefix parser =

ws (skipStringCI prefix) >>. ws (skipChar ':') >>. parser .>> opt newline

let specificationName : Parser<ProblemComponent, unit> =

parseSpecification "NAME" tillEndOfLine

|>> Name.apply

|>> ProblemComponent.SpecificationName

<!> "NAME"

The |>> combinator creates a parser which effectively feeds the output of a parser on its left into a function on its right. This is generally how one creates a parser that returns an instance of the AST type.

Just ignore the ProblemComponent type for now.

Reusing Parsers

It’s instructive to notice that we have already written the bits for any simple-valued key-value specification. Using the same definitions we have had so far, and appropriate ASTs, we can build parsers for the Comment string value; and the Dimension and Capacity integer values.

let specificationComment : Parser<ProblemComponent, unit> =

parseSpecification "COMMENT" tillEndOfLine

|>> Comment.apply

|>> ProblemComponent.SpecificationComment

<!> "COMMENT"

let specificationDimension : Parser<ProblemComponent, unit> =

parseSpecification "DIMENSION" (pint32 .>> newline)

|>> Dimension.apply

|>> ProblemComponent.SpecificationDimension

<!> "DIMENSION"

let specificationCapacity : Parser<ProblemComponent, unit> =

parseSpecification "CAPACITY" (pint32 .>> newline)

|>> CVRPCapacity.apply

|>> ProblemComponent.SpecificationCVRPCapacity

<!> "CAPACITY"

Debugging Parsers

Pay attention to the <!> combinator. We define this special utility combinator as follows:

let (<!>) (p: Parser<_,_>) label : Parser<_,_> =

#if true && PARSER_TRACE

fun stream ->

printfn $"{stream.Position}: Entering {label}"

let reply = p stream

printfn $"{stream.Position}: Leaving {label} ({reply.Status})"

reply

#else

p <?> label

#endif

This is how we debug parsers. This utility parser can be made to emit a trace of which parser encountered what, and whether it successfull matched a pattern or not. A less-verbose implementation would be to simply tag a parser with the built-in <?> combinator.

Constraining values to an enumeration

The parser needs to become a little smarter when we consider the Type keyword. The string value can’t be any string, but one of the specified choices. F#’s union types simplifies this for us. We will create a union type with the appropriate tags as follows:

type ProblemType =

| TSP

| ATSP

| SOP

| HCP

| CVRP

| TOUR

We then write a parser for each value as follows:

let specificationType =

choice

[

wstr "TSP" >>. preturn TSP

wstr "ATSP" >>. preturn ATSP

wstr "SOP" >>. preturn SOP

wstr "HCP" >>. preturn HCP

wstr "CVRP" >>. preturn CVRP

wstr "TOUR" >>. preturn TOUR

]

|> parseSpecification "TYPE"

|>> ProblemComponent.SpecificationType

<!> "TYPE"

The following points will help you make sense of what’s going on

- The

wstrparser matches a literal string - The

preturnparser simply returns the corresponding union type tag - The

>>.combinator pairs the string parser with its return value, ignoring the matched string and preserving the tag - The

choicecombinator matches any one of the provided parsers with the value, and fails if none matches - The

parseSpecificationcombinator wraps each of the parsers with the appropriate space and colon handling parsers and matches theTYPEkeyword

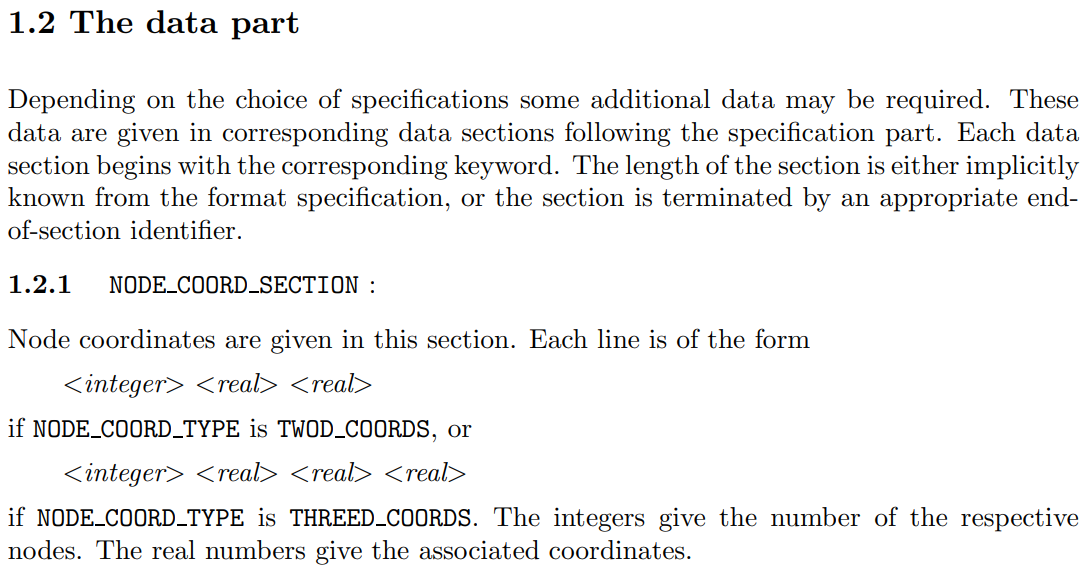

Reading Data Blocks

The “Data Part” of the TSP file is a group of Sections, which have rather a different format to the Specifications, and is quite complex because there may be multiple formats to read in each section itself:

We follow much the same approach as with a specification, except because data are provided on a variable number of lines, we grab lists of data until we read a line with a delimiter on it.

For example, considering the “Node Coord Section” specified above, we define the following types and parsers:

type NodeId = private | NodeId of int32

with

static member directApply x = NodeId x

static member zeroBasedApply x = NodeId (x + 1)

member this.zeroBasedUnapply = match this with | NodeId x -> (x - 1)

type Coordinate = | Coordinate of float

with

member inline this.unapply = match this with Coordinate x -> x

type NodeCoord2D = { NodeId : NodeId; X : Coordinate; Y : Coordinate }

with

static member apply ((nodeId, x), y) = { NodeId = nodeId; X = x; Y = y }

and NodeCoord3D = { NodeId : NodeId; X : Coordinate; Y : Coordinate; Z : Coordinate}

with

static member apply (((nodeId, x), y), z) = { NodeId = nodeId; X = x; Y = y; Z = z }

and NodeCoordSection =

| Nodes2D of NodeCoord2D list

| Nodes3D of NodeCoord3D list

let NodeId =

ws_x_nl pint32

|>> NodeId.directApply

<!> "NodeId"

let Coordinate =

ws_x_nl pfloat <|> ws_x_nl (pint32 |>> float)

|>> Coordinate.Coordinate

<!> "Coordinate"

let NodeCoord2D =

NodeId .>>. Coordinate .>>. Coordinate .>> newline

|>> NodeCoord2D.apply

<!> "Coord2D"

let NodeCoord3D =

NodeId .>>. Coordinate .>>. Coordinate .>>. Coordinate .>> newline

|>> NodeCoord3D.apply

<!> "Coord3D"

let sectionNodeCoord : Parser<ProblemComponent, unit> =

let Nodes2D = many NodeCoord2D |>> NodeCoordSection.Nodes2D

let Nodes3D = many NodeCoord3D |>> NodeCoordSection.Nodes3D

wstr "NODE_COORD_SECTION" >>. (Nodes2D <|> Nodes3D)

|>> ProblemComponent.SectionNodeCoords

<!> "NODE_COORD_SECTION"

Almost all the parser combinators encountered here have been encountered before.

The .>>. combinator combines the parser to its left with the parser to its right, and constructs a tuple with the output of both as its own output. Repeatedly using the .>>. combinator will result in a set of nested 2-tuples. It is handy to have the .apply pattern to be able to consume this convoluted form, as seen above.

Strong-Typing for Correct Semantics

The other thing to note is that the TSP problem domain numbers cities in a 1-based numbering scheme; It is often useful in code to use a 0- based index. To keep things clean and not introduce “off-by-one” errors, we can use strong-typing to indicate that any value of type NodeId is implicitly 1- based; and further, because we don’t support mathematical operations on NodeId, we cannot do nonsensical things like add two city indices together! Strong-typing turns out to be very useful here to aid in the correctness and maintainability of our program.

Of course, the data being parsed will all be 1- based, so we have a special constructor function for use in the parser, and different constructor and decomposer functions for use in other contexts.

Matching keywords in any order

This turns out to be a tricky requirement, specially because the keywords may arrive in any order but some keywords may be affected by the presence or absence of other keywords.

We will solve this by blindly parsing all the key-value pairs into a single list; build up a data structure with the individual items; and then semantically validate the resulting data structure.

Of course, creating a list of components means that every parser needs to generate the same type. So we create another union type representing problem components.

type ProblemComponent =

| SpecificationName of Name

| SpecificationComment of Comment

| SpecificationType of ProblemType

| SpecificationDimension of Dimension

| SpecificationCVRPCapacity of CVRPCapacity

| SpecificationEdgeWeightType of EdgeWeightType

| SpecificationEdgeWeightFormat of EdgeWeightFormat

| SpecificationEdgeDataFormat of EdgeDataFormat

| SpecificationNodeCoordType of NodeCoordType

| SpecificationDataDisplayType of DataDisplayType

| SectionNodeCoords of NodeCoordSection

| SectionDepots of DepotsSection

| SectionDemands of DemandsSection

| SectionEdgeData of EdgeDataSection

| SectionFixedEdges of FixedEdgesSection

| SectionDisplayData of DisplayDataSection

| SectionTours of ToursSection

| SectionEdgeWeights of EdgeWeightSection

| SectionEof of EofSection

This is why the specificationName parser above, for example, eventually called the |>> ProblemComponent.SpecificationName combinator.

Now, we have to read the whole file, and try to get each parser to match its corresponding section.

let parseProblem =

[

specificationName

specificationType

specificationComment

specificationDimension

specificationCapacity

specificationEdgeWeightType

specificationEdgeWeightFormat

specificationEdgeDataFormat

specificationNodeCoordType

specificationDataDisplayType

sectionNodeCoord

sectionDepots

sectionDemands

sectionEdgeData

sectionFixedEdges

sectionDisplayData

sectionTours

sectionEdgeWeight

sectionEof

]

|> Seq.map attempt

|> choice

|> many

|>> ProblemComponent.coalesce

<!> "Problem"

The attempt combinator tries to apply a parser, and considers it a non-fatal error if the parser fails because we’re looking at a different section at that time.

The choice combinator, also seen before as <|>, picks combinators one at a time until one succeeds.

The many combinator repeats until as many matches as possible are found.

At this point, we have constructed a single complex parser combinator which consumes a full document and gives us a list of ProblemComponents. We’ll transform that list into a single record - the full AST type for the TSP Problem - with an elegant little fold that takes an “empty” Problem as the seed, and successively fills out a matching field for each value it encounters in the list.

type Problem =

{

Name : Name option

Comment : Comment option

Type : ProblemType option

Dimension : Dimension option

EdgeWeightType : EdgeWeightType option

CVRPCapacity : CVRPCapacity option

EdgeWeightFormat : EdgeWeightFormat option

EdgeDataFormat : EdgeDataFormat option

NodeCoordType : NodeCoordType option

DataDisplayType : DataDisplayType option

NodeCoordSection : NodeCoordSection option

DepotsSection : DepotsSection option

DemandsSection : DemandsSection option

EdgeDataSection : EdgeDataSection option

FixedEdgesSection : FixedEdgesSection option

DisplayDataSection : DisplayDataSection option

ToursSection : ToursSection option

EdgeWeightSection : EdgeWeightSection option

EofSection : EofSection option

}

with

static member coalesce =

List.fold

(

fun (problem : Problem) -> function

| SpecificationName c -> { problem with Name = Some c }

| SpecificationComment c -> { problem with Comment = Some c }

| SpecificationType c -> { problem with Type = Some c }

| SpecificationDimension c -> { problem with Dimension = Some c }

| SpecificationCVRPCapacity c -> { problem with CVRPCapacity = Some c }

| SpecificationEdgeWeightType c -> { problem with EdgeWeightType = Some c }

| SpecificationEdgeWeightFormat c -> { problem with EdgeWeightFormat = Some c }

| SpecificationEdgeDataFormat c -> { problem with EdgeDataFormat = Some c }

| SpecificationNodeCoordType c -> { problem with NodeCoordType = Some c }

| SpecificationDataDisplayType c -> { problem with DataDisplayType = Some c }

| SectionNodeCoords c -> { problem with NodeCoordSection = Some c }

| SectionDepots c -> { problem with DepotsSection = Some c }

| SectionDemands c -> { problem with DemandsSection = Some c }

| SectionEdgeData c -> { problem with EdgeDataSection = Some c }

| SectionFixedEdges c -> { problem with FixedEdgesSection = Some c }

| SectionDisplayData c -> { problem with DisplayDataSection = Some c }

| SectionTours c -> { problem with ToursSection = Some c }

| SectionEdgeWeights c -> { problem with EdgeWeightSection = Some c }

| SectionEof c -> { problem with EofSection = Some c }

)

Problem.zero

Note that each of the members in the Problem AST is an option because we’re going to construct this record incrementally from a list, and because items may show up in any order.

There is still no guarantee that this structure represents a valid or consistent problem, but now we can run validations on the whole structure instead of having to deduce correctness one section at a time.

Tying it all together

We started this post with the WeightedCompleteGraph data structure, because that gave us the adjacency matrix we could use for our distance calculations.

And this is where the fun begins, because in some formats, like the “Node Coord” example above, the distances need to be computed from the coordinates provided, so we may have to do some significant computation based on the problem input to get to a standard graph that we can examine for Hamiltonian Cycles.

Let’s stick with the “Node Coord” example, and write the transformation for 2d coordinates:

First, we’ll augment the NodeCoord2D type with the specified mathematics for computing coordinate distances:

type NodeCoord2D = { NodeId : NodeId; X : Coordinate; Y : Coordinate }

with

static member apply ((nodeId, x), y) = { NodeId = nodeId; X = x; Y = y }

static member private L2 (i : NodeCoord2D, j : NodeCoord2D) =

let xd = i.X - j.X

let yd = i.Y - j.Y

(xd * xd) + (yd * yd)

|> sqrt

static member EuclideanDistance =

NodeCoord2D.L2 >> int32

static member CeilingEuclideanDistance =

NodeCoord2D.L2 >> ceil >> int32

static member PseudoEuclideanDistance (i : NodeCoord2D, j : NodeCoord2D) =

let xd = i.X - j.X

let yd = i.Y - j.Y

let rij = sqrt ((xd * xd) + (yd * yd) / 10.0)

let tij = floor rij

int32 (if tij < rij then tij + 1.0 else tij)

static member ManhattanDistance (i : NodeCoord2D, j : NodeCoord2D) =

let xd = i.X - j.X |> abs

let yd = i.Y - j.Y |> abs

xd + yd

|> int32

static member MaximumDistance (i : NodeCoord2D, j : NodeCoord2D) =

let xd = i.X - j.X |> abs |> int32

let yd = i.Y - j.Y |> abs |> int32

max xd yd

static member GeographicalDistance (i : NodeCoord2D, j : NodeCoord2D) =

let RRR = 6378.388

let toRadians (f : float) =

let deg = floor f

let min = f - deg

System.Math.PI * (deg + 5.0 * min / 3.0) / 180.0

let (lat_i, long_i) = (toRadians i.X.unapply, toRadians i.Y.unapply)

let (lat_j, long_j) = (toRadians j.X.unapply, toRadians j.Y.unapply)

let q1 = long_i - long_j |> cos

let q2 = lat_i - lat_j |> cos

let q3 = lat_i + lat_j |> cos

let f = 0.5*((1.0+q1)*q2 - (1.0-q1)*q3) |> acos

RRR * f + 1.0

|> int32

Then, given the coordinates for each city, we will generate the matrix with the distances between all cities:

let toWeightedCompleteGraph (problem : Problem) : WeightedCompleteGraph option =

let computeEdgeWeights (f2, f3) (problem : Problem) (g : WeightedCompleteGraph) : WeightedCompleteGraph option =

let dim = g.Dimension.unapply

let computeEdgeWeight (weight_func : ('n * 'n -> int) option) (unapply : 'n -> int) (nodes : 'n list) =

option {

let! f = weight_func

let m = nodes |> List.map (fun n -> (unapply n, n)) |> Map.ofList

for p1 in 0 .. (dim - 1) do

for p2 in 0 .. (dim - 1) do

let d = f (m[p1], m[p2])

g[NodeId.zeroBasedApply p2, NodeId.zeroBasedApply p1] <- Weight d

return g

}

problem.NodeCoordSection

|> Option.bind (function

| NodeCoordSection.Nodes2D nodes -> computeEdgeWeight f2 (fun (n : NodeCoord2D) -> n.NodeId.zeroBasedUnapply) nodes

| NodeCoordSection.Nodes3D nodes -> computeEdgeWeight f3 (fun (n : NodeCoord3D) -> n.NodeId.zeroBasedUnapply) nodes)

option {

let! name = problem.Name

let! comment = problem.Comment

let! dimension = problem.Dimension

let! problemType = problem.Type

let! edgeWeightType = problem.EdgeWeightType

let g = WeightedCompleteGraph (name, problemType, comment, dimension)

return!

match edgeWeightType with

| EUC_2D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.EuclideanDistance, Some NodeCoord3D.EuclideanDistance) problem g

| EUC_3D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.EuclideanDistance, Some NodeCoord3D.EuclideanDistance) problem g

| MAX_2D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.MaximumDistance, Some NodeCoord3D.MaximumDistance) problem g

| MAX_3D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.MaximumDistance, Some NodeCoord3D.MaximumDistance) problem g

| MAN_2D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.ManhattanDistance, Some NodeCoord3D.ManhattanDistance) problem g

| MAN_3D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.ManhattanDistance, Some NodeCoord3D.ManhattanDistance) problem g

| CEIL_2D -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.CeilingEuclideanDistance, None) problem g

| GEO -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.GeographicalDistance, None) problem g

| ATT -> computeEdgeWeights (Some NodeCoord2D.PseudoEuclideanDistance, None) problem g

// other edge weight types elided

}

let parseTextToWeightedCompleteGraph str =

match run parseWeightedCompleteGraph str with

| Success(result, _, _) -> result

| Failure(err, _, _) -> sprintf "Failure:%s[%s]" str err |> failwith

The following points are noteworthy here:

Option as a monad

This is an example where using monadic composition vastly simplifies the code.

We are going through and constructing a WeightedCompleteGraph from a Problem. If you recall, every property of Problem is set up to be an option because we have to construct it incrementally from a list, and there are legitimate cases where a property may not have a value. But as we copy over the properties now, we have to write code that fails if one of the mandatory properties does not exist. The cleanest way to do this is to use the CE pattern to monadically compose the assignments.

Functional abstraction

We have multiple ways of computing distances depending on how the data need to be interpreted. But applying those computations can be done uniformly by abstracting at the right level. In this case, we have a single function that does the iteration over the city-pairs, and we pass in the distance computing functions as arguments to that function, so we can have a terse and clean implementation of computing the matrix

Off-by-one errors begone

By lifting the city identifier to its own type NodeId and not treating it like a raw integer, we can securely and correctly lift the 0- based iteration index into the 1- based city index without causing any head-scratching for maintainers that look at this code next year. After all, adding 1 to a city index really doesn’t make any sense!

Handle 2D and 3D cases uniformly

Organizing this code in this fashion even allows us to delegate the distance computation to the coordinate type and judiciously using the Option type, we can reuse the same iteration driver function computeEdgeWeight to handle cases for which comptutations are specified for both 2D and 3D coordinates, and cases where computations are only specified for 2D coordinates (see the GEO case)

Driving the Parser

Once the parser that generates the WeightedCompleteGraph is complete, we need to write a top level function that parses a given file into a WeightedCompleteGraph. This becomes the “API” of the parser, if you like.

Here’s a suitable driver function which parses a string to a WeightedCompleteGraph, and a test snippet which runs that on an actual data file from TSPLib and prints the parsed result.

And we’re done!

let parseTextToWeightedCompleteGraph str =

match run parseWeightedCompleteGraph str with

| Success(result, _, _) -> result

| Failure(err, _, _) -> sprintf "Failure:%s[%s]" str err |> failwith

let dataRoot = @"C:\code\TSP\tspsolver\data\tsplib95"

let input =

[| dataRoot; "att48.tsp" |]

|> System.IO.Path.Combine

|> System.IO.File.ReadAllText

parseTextToWeightedCompleteGraph input

|> printfn "%O"

Conclusion

-

We started with the problem of trying to read data published in a loosely-specified domain-specific-language, so that we could represent it in a manner that allows us to solve the TSP.

-

We then approached the problem functionally with parser-combinators, and developed incrementally complex parsers to allow us to process and consume the complete variety of input formats. We allowed for optional sections, and sections in any order. We included mechanisms for tracing the parser to aid in debugging.

-

We then applied the specified computations to transform some formats of data where only coordinates were specified into appropriate edge-weights for a complete graph. We did this in a manner that would safely fail if the data were missing important details (i.e. if the specified data were inconsistent).

-

We developed this incrementally. Practically, this means writing small test snippets and exercising the parsers at the time of development using FSI. One of the consequences of strong typing in this specific case is that parsing failures are dealt with at compile time, not discovered at run-time as with some other languages.

-

We did all of this in a few hundred lines of code.

The primary thesis of this post is that even mundane tasks such as parsing and processing input data can be done tersely, elegantly and safely in F#.

The secondary use of this might be as a useful practical reference of how to write a non-trivial parser.

Next, we’ll look at Genetic Algorithms and how to write those in F#.

Keep typing! :)