Introduction

This post outlines the implementation of a specific approach to Genetic Algorithms. I will give some introductory insights along the way, but this post is not meant to be a general introduction to Genetic Algorithms. There is a wealth of information available about Genetic Algorithms available for further context.

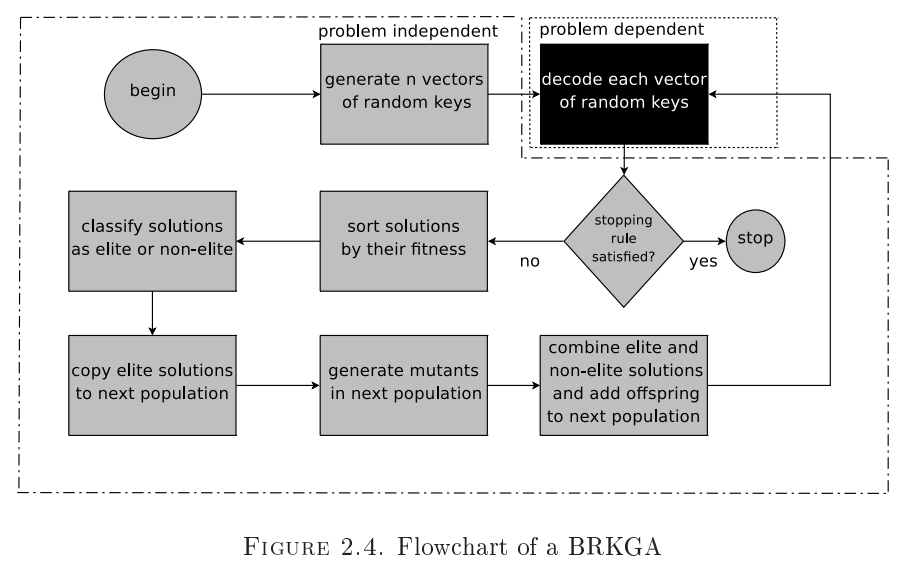

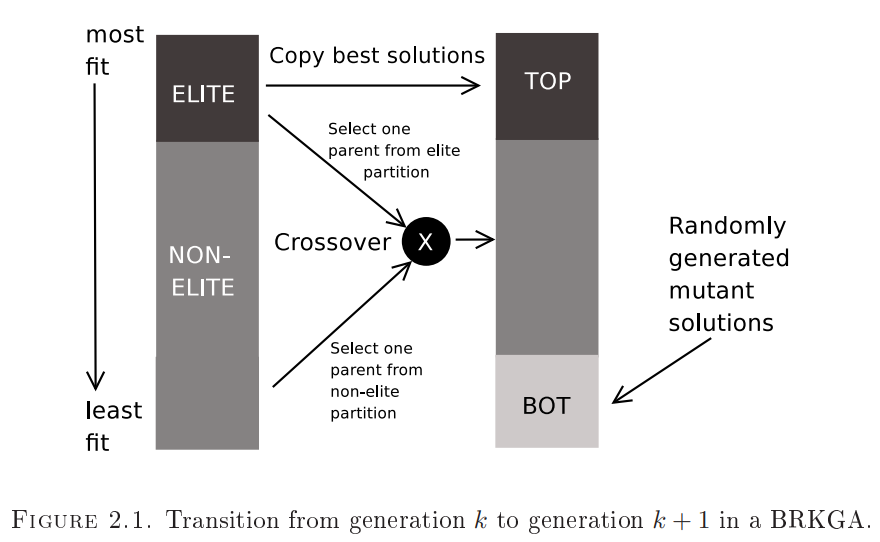

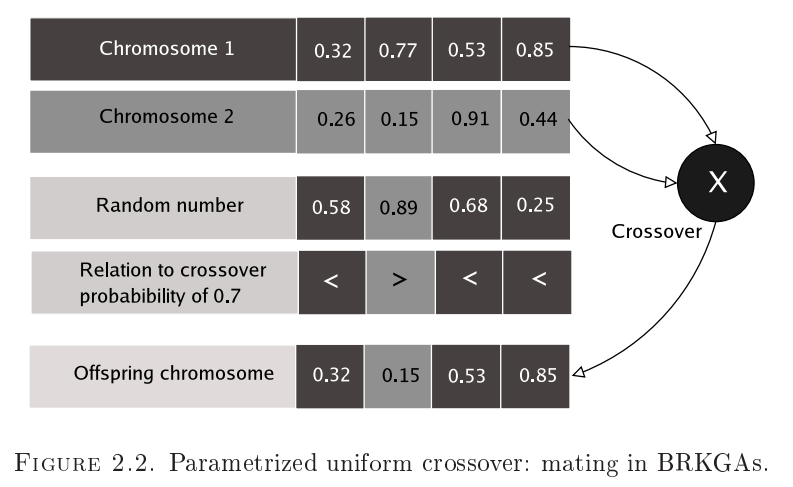

We are first going to implement the BRKGA as outlined in this paper and with supporting information from this presentation.

All following images are taken from the above references:

Overview of Evolutionary Genetic Algorithms

This is a class of nature-inspired algorithms which attempt to evolve solutions optimized for some given fitness function.

- The key structure in a genetic algorithm is a chromosome, which is a string of individual genes. A fitness function computes the associated fitness of a chromosome.

- There may be one or more ways to replace some genes of a chromosome with others, effectively modelling mutation.

- There may be one or more ways to combine (aka crossover) genes from two or more chromosome to yield one or more new chromosomes which now have characteristics of their ancestors.

- Starting with a population of randomly generated chromosomes, the fitness of each chromosome is calculated, and a new generation of chromosomes can be evolved by judiciously applying mutation and crossover operators to yield a population that has possibly fitter chromosomes than the previous generation. This is done repeatedly, and the observation is that over time, chromosomes evolve that are locally or globally optimally fit.

- Encoding a problem to solve into a scheme of chromosomes and operators is an exercise in innovation, creativity and intuition.

- The resultant solution that evolves doesn’t explicitly exploit any characteristics of the problem itself - just that a fitter solution is implictly chosen and potentially improved over time. Consequently there is no guarantee that one will get a perfect solution everytime, but one can choose schemes to ensure that the population doesn’t regress.

- In contrast with other approaches to solve NP-complete problems that take a lot of computational time to achieve even heuristically approximate solutions whilst exploiting some property of the problem itself, this approach generally is computationally lightweight, and one can stop an evolution saga at any stage and start over again if the best solution found is insufficiently sub-optimal.

The BRKGA is one such evolutionary genetic algorithm that takes advantage of several schemes to empirically achieve good results.

Overview of BRKGA

With classic BRKGA, the following refinements apply

- All genes are of type

float. Consequently, all chromosomes are fixed length arrays offloatvalues - The encoding and decoding operations play a critical role in BRKGA.

- The encoding of a problem into an array of

floats allows the mechanics of evolution to be uniformly and problem-agnostic. - The fitness of a chromosome requires the decoding of the array into

floats into a problem-specific representation whose fitness can be computed properly.

- The encoding of a problem into an array of

- The remaining genetic operations take place in the space of

floats. - A clever mechanism of evolution is employed to generate the next generation of chromosomes as follows:

- A proportion of the old population, comprising the elite chromosomes with the best fitness, are copied over unchanged to the new generation. This ensures that the best fitness of the next generation cannot be worse than the best fitness of this one.

- A proportion of the new population is made up of fresh randomly generated chromosomes - mutants - in an attempt to introduce randomness to allow the solution to break over local fitness extrema.

- The rest of the new population is made up of children which are generated between one elite parent and one non-elite parent of this generation. The individual genes of each children are selected randomly from the genes of its parents, biasing for selection of more genes from the elite parent. This approach attempts to pick more characteristics of the elite parent for each child.

- Empirically, there seems to be correspondence between this approach and some variant of learning, as the evolved generations converge rather rapidly towards fitness.

The F# Implementation

The beauty of this paper is that one can almost literally extract the core code from it, but we can do some nice things with F#.

It’s important to note that this implementation is completely problem-agnostic. We can use this implementation to apply the BRKGA approach to any problem we choose.

Chromosome

type Chromosome = private { Genes' : float[]; Length' : ChromosomeLength }

with

member this.Genes = this.Genes'

member this.Length = this.Length'

static member Random (length : ChromosomeLength) =

let genes =

[|

for _ in 0 .. (length.unapply - 1) ->

rand.NextDouble()

|]

{ Genes' = genes; Length' = length }

static member Apply (genes : float[]) =

{ Genes' = genes; Length' = ChromosomeLength genes.Length }

The reason we use a private constructor for this type is a consequence of an F# typing limitation. The requirement we really need to satisfy is that the Chromosome needs to have a specified array length, and just allowing unfettered access to the structure would allow someone to construct chromosomes of any size.

The ideal solution would be to have a dependent type system where the chromosome length can be part of the type specification, but F# does not yet support this, so we have to make do with makeshift protections.

The first use case is to create a random chromosome of specified length, and this is implemented in the Chromosome.Random extension method.

The next use case is to be able to create a chromosome with specified genes, which is implemented in the Chromosome.Apply method.

TaggedChromosome

Because we do a lot of decoding during the evolution process, I found that it was easier to just keep both the decoded and encoded versions together with the fitness - trading space for time seems to work for the sizes we’re talking about.

type TaggedChromosome<'t> = { Chromosome : Chromosome; Fitness : Fitness; Tag : 't }

with

static member inline FitnessSelector cwf = cwf.Fitness

static member inline apply<'t> (decodeFunction : Decoder<'t>) (fitnessFunction : FitnessFunction<'t>) (chromosome : Chromosome) =

let tag = chromosome |> decodeFunction

let fitness = tag |> fitnessFunction

{ Chromosome = chromosome; Fitness = fitness; Tag = tag }

and Encoder<'t> = 't -> Chromosome

and Decoder<'t> = Chromosome -> 't

and FitnessFunction<'t> = 't -> Fitness

Population

Again, it would’ve been awesome to have the ability to specify the chromosome length as a type parameter to this type, but we can’t do that yet. We again specify the type constructor to be private, so we can ensure that it’s always sorted in such a way that the chromosome with the best fitness is easy to access.

Stunningly, this is the entire definition, complete with the code to evolve the population to the next generation

type Population<'t when 't : comparison> = private | Population of TaggedChromosome<'t>[]

with

member this.Unapply = match this with Population x -> x

member this.Best = this.Unapply[0]

static member GetRandomChromosomes (pp : PopulationParameters<'t>) n =

let random _ =

Chromosome.Random pp.ChromosomeLength

|> TaggedChromosome.apply<'t> pp.DecodeFunction pp.FitnessFunction

[| for i in 0 .. (n - 1) -> random i |]

|> Array.sortBy TaggedChromosome<'t>.FitnessSelector

static member Random (pp : PopulationParameters<'t>) =

Population.GetRandomChromosomes pp pp.InitialPopulationCount.unapply

|> Population

member this.Evolve (pp : PopulationParameters<'t>) (ep : EvolutionParameters) =

let populationCount = pp.InitialPopulationCount.unapply

let members = this.Unapply

let eliteCount = proportion members.Length ep.ElitePercentage

let mutantCount = proportion populationCount ep.MutantPercentage

let childrenCount = populationCount - (eliteCount + mutantCount)

let inline pickRandom (min, max) =

members[System.Random.Shared.Next(min, max)]

let elites =

members |> Array.take eliteCount

let mutants =

Population.GetRandomChromosomes pp mutantCount

let children =

let crossover (elite, other) =

elite.Chromosome.ParametrizedUniformCrossover ep.EliteBias other.Chromosome

|> TaggedChromosome.apply<'t> pp.DecodeFunction pp.FitnessFunction

[|

for _ in 0 .. (childrenCount - 1) ->

(pickRandom (0, eliteCount), pickRandom (eliteCount, members.Length))

|]

|> Array.Parallel.map crossover

[| elites; children; mutants |]

|> Array.concat

|> Array.sortBy TaggedChromosome<_>.FitnessSelector

|> Population

It’s almost embarrassingly simple to read, and it almost trivially corresponds with the specifications in the paper

Hyper Parameters

Of course, we want to run the evolution process multiple times, to allow for the solution to converge. This means that we want to encapsulate those parameters neatly. I’ve split them into two parts - one of which has the recommended defaults and is problem-agnostic, and the other which is type-parameterized with the problem type and is therefore problem-specific.

type PopulationParameters<'t> = {

ChromosomeLength : ChromosomeLength

InitialPopulationCount : PopulationCount

EncodeFunction : Encoder<'t>

DecodeFunction : Decoder<'t>

FitnessFunction : FitnessFunction<'t>

}

type EvolutionParameters = private {

ElitePercentage : double

MutantPercentage : double

EliteBias : double

}

with

static member Default =

EvolutionParameters.Initialize 0.25 0.15 0.75

Drivers

We are interested in the convergence pattern of the algorithm, so it isn’t sufficient to just get the best fitness at the end of all the iterations. Rather, we want to track how the best fitness improves (or not) with each iteration…

So we will build an emit a CSV as the result of the experiment, enabling us to plot the information out of band.

I’ve split this into two functions - one to do the iteration, and one to emit the CSV. We use an anonymous record to transmit the data from the first function to the second.

let inline private SolveInternal<'t when 't : comparison> (populationParameters : PopulationParameters<'t>) (evolutionParameters : EvolutionParameters) (num_iterations : int) =

let outerTime, innerTime = System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch(), System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch();

let dot = num_iterations / 100

outerTime.Start()

let mutable population = Population.Random populationParameters

let initial = population.Best

let results =

[|

for i in 0 .. num_iterations ->

if i % dot = 0 then printf "."

innerTime.Restart()

population <- population.Evolve populationParameters evolutionParameters

innerTime.Stop()

{| Iteration = i; IterationTime = innerTime.ElapsedMilliseconds; BestFitness = population.Best.Fitness |}

|]

printfn ""

outerTime.Stop()

{| TotalTime = outerTime.ElapsedMilliseconds; Results = results; Initial = initial; Final = population.Best |}

let Solve<'t when 't : comparison> (experimentName : string) (populationParameters : PopulationParameters<'t>) (evolutionParameters : EvolutionParameters) (num_iterations : int) =

let results = SolveInternal<'t> populationParameters evolutionParameters num_iterations

let fileName = (FileInfo $"BRKGA_Classic_{experimentName}_{System.DateTime.Now.Ticks}.csv").FullName

let output = new StreamWriter(fileName)

let emit (s : string) =

output.WriteLine s

try

emit <| $"# {{ Experiment : {experimentName}; Iterations : {num_iterations}; Runtime (ms) : {results.TotalTime}; }}"

emit <| $"# {{ HyperParameters : %O{evolutionParameters} }}"

emit <| $"# {{ Population : {populationParameters.InitialPopulationCount}; InitialFitness : %O{results.Initial.Fitness}; FinalFitness : %O{results.Final.Fitness} }}"

emit <| $"# {{ DecodedChromosome : %O{results.Final.Tag} }}"

emit <| "Iteration, Fitness, Time"

for r in results.Results |> Array.sortBy (fun t -> t.Iteration) do

emit <| $"{r.Iteration}, %O{r.BestFitness}, {r.IterationTime}"

printfn $"# {{ Experiment : {experimentName}; Iterations : {num_iterations}; Runtime (ms) : {results.TotalTime}; }}"

printfn $"# {{ HyperParameters : %O{evolutionParameters} }}"

printfn $"# {{ Population : {populationParameters.InitialPopulationCount}; InitialFitness : %O{results.Initial.Fitness}; FinalFitness : %O{results.Final.Fitness} }}"

printfn $"# {{ DecodedChromosome : %O{results.Final.Tag} }}"

printfn $"Wrote results to {fileName}"

finally

output.Flush ()

output.Close ()

Conclusions

-

We started with the problem of implementing a problem-agnostic evolutionary genetic algorithm approach.

-

We leveraged the F# type system and terse syntax to implement the algorithm in a clear, readable manner. The implementation we have is under 200 lines of code.

-

F# could have improved this by having dependent type parameters. Rust has this as part of its language specification, and it would be instructive to write this algorithm in Rust for comparison.

Next, we’ll look at solving the TSP in this fashion.

Keep typing! :)