This blog post is homage to Jim Weirich and his contribution to the FP community in general - and the Ruby community in particular. Jim was a skilled and effective communicator, and his video helped me get started on grokking the Y-combinator.

I dedicate this blog post to Prof. Neeldhara Misra whose friendship and encouragement I have come to rely on! Thank you for re-igniting a passion to learn, explore, and teach! Keep walking!

- 1. Introduction

- 2. First steps

- 3. It’s continuations all the way down

- 4 The Lambda Calculus

- 5 Curing Schizophrenia

- 6 Lifting Heavy Things…

- 7. Conclusion

1. Introduction

When I was taught programming back in my high school and undergraduate days, goto, for-loops and while-loops were taught as a fundamental building blocks for control-flow. It was unthinkable to me in those early days that one could have a programming language that had none of these primitives in it; and I humbly posit that things haven’t really changed much in introductory programming courses these days.

Of course, once we were taught that you could have a function which called another function, then the natural question to ask was “can a function call itself”. I’m old enough to have encountered languages where this was not possible, but modern languages like Pascal and C allowed a function to call itself, and that led to very elegant implementations of self-referential data structures like linked lists and graphs. So recursion was introduced as a language feature.

Later, in my undergraduate days, we were introduced to LISP and LISP-like languages which primarily used recursion for control-flow; for- and while- loops were actually syntactic sugar over forms of recursion, offering a glimpse of an insight that recursion was somewhat more fundamental than we’d recognized that far. I invite you to dive into a secondary rabbit hole of expressivity in languages at your leisure.

In the software development industry, where I made most of my career, there is an ill-founded reticence to use recursion - allegedly for performance reasons, but really because recursion is more feared than understood. Some advanced algorithms like graph and tree traversals are painstakingly written out iteratively because there’s a laughably naive notion that this way is somehow better, belying the true power and elegance of recursion. I’ve addressed some of these misconceptions and FP remedies before.

So, let’s accept that recursion is beautiful and elegant, and actually more fundamental than other control structures (although perhaps not the most fundamental of all).

But where does it come from? And can we somehow derive it from first principles? That is what this blog post is about.

I strongly recommend reading this post in conjuction with Jim Weirich’s video and an open F# Interactive Window, working through the individual steps. The “a-ha” moment is well-worth working towards! It is not coincidental that this blog post follows the video closely, and I gladly acknowledge Jim’s efforts in trying to make this tricky concept clear. All I’ve done is try to put it into the F# context and address some of the mechanics of adapting to a strongly-typed language!

2. First steps

At some point in your F# coding - possibly very early on - you’ll encounter a let rec binding, because without the rec, the function being defined can’t be called within its definition. So this code compiles:

let rec fact =

function

| 0 -> 1

| n -> n * fact (n - 1)

I use this example with reticence - I agree with Dr. Shriram Krishnamurti that this isn’t the best way to teach recursion - but given that it is 1) easily understandable - if not relatable - and 2) doesn’t have any associated data structures, it makes the mechanical steps we are going to perform a little easier.

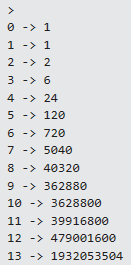

In fact, you can invoke this function and it will eventually return the required factorial:

fact 10 // returns 3628800

Now, let rec is clearly a language construct: it’s a way to tell the F# compiler that the binding should be deferred until the definition is complete, so that the function can invoke itself. But that’s not really a good explanation of how recursion itself is derived. So let’s dig a little further and see if we can derive a way to do recursion without let rec.

3. It’s continuations all the way down

Well, functions can call functions, and functions are first-class items so they can be passed in as function arguments, so why not just pass in the function we want to call as an argument and just call that?

3.1 Mind the first step, it’s a doozy!

let f omega =

(fun x ->

match x with

| 0 -> 1

| n -> n * (omega (n - 1)))

Let’s unpack this carefully here: f is a function, which takes omega as a single argument, and returns an anonymous function which takes one integer argument and has the recursive form of the factorial function as its body - except that it calls omega instead of itself. omega here is a continuation, which, loosely, is just a fancy way of saying “here, call this function when you want to move on”!

Now this only syntactically looks like a recursive function - there’s no recursion happening here. In fact, since the only restriction on omega is that it should be invoked with a single integer argument, we can actually pass in any old function that fulfils that requirement.

let error x = failwith $"{x} goes Boom!"

Here, error is a function that takes an argument and just throws an exception. We can pass it in to f, and this happens:

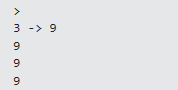

let fact0 = f (error)

fact0 0 // returns 1

fact0 1 // "0 goes Boom!"

Let us carefully understand why it works like this: f error (aka fact0) is a function which takes a single integer argument and matches it against 0 (returning 1), or anything else (where it tries to multiply its argument with the result of omega invoked on the next smaller number).

So when we invoke fact0 with 0, the match condition triggers a valid return; but when we invoke it with 1, the match condition triggers a call to omega. In our case, the omega passed in is error, which ignores whatever argument is passed in and throws an exception instead.

(It’s worth pointing out that functional programmers love total functions, and so eschew exceptions because functions which throw don’t return a value for all arguments like well-behaved functions do. I’m deliberately throwing an exception here to violently jar us from a state of complacence - to show that something undesirable needs to be dealt with. We’ll get rid of this behaviour soon, so just excuse it for now!)

3.2 Oh look, a rabbit hole!

Now that we’ve understood why there’s no mystery at all to this behaviour, let’s take the next step:

Remember that fact0, just like error, is a function that takes a single argument. So why can’t we pass that into f instead?

let fact1 = f fact0

fact1 0 // returns 1

fact1 1 // returns 1

fact1 2 // "0 goes Boom!"

And indeed, because we’re on a roll here, let’s go one further:

let fact2 = f fact1

fact2 0 // returns 1

fact2 1 // returns 1

fact2 2 // returns 2

fact2 3 // "0 goes Boom!"

I encourage you to actually try this to see that it actually seems to be starting to calculate the factorial. Then come back and see if this explanation of why it works is reasonable:

Given:

let f omega = (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * omega (n - 1))

let error x = failwith $"{x} goes Boom!"

let fact0 = f (error)

let fact1 = f (fact0)

let fact2 = f (fact1)

We can expand out the fact2 definition:

let fact2 =

(f fact1) // textually replace fact2 with its expression

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * fact1 (n - 1)) // textually replace f with its expression and replace the omega argument with fact1

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * (f fact0) (n - 1)) // textually replace fact1 with its expression

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * (fun x' -> match x' with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * fact0 (n'-1)) (n - 1)) // textually replace f with its expression, renaming n to n', and replace the omega argument with fact0

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * fact0 (n'-1)) // textually replace the x' argument with (n - 1)

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * (f error)(n'-1)) // textually replace fact0 with its expression

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * (fun x' -> match x' with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))(n'-1)) // // textually replace f with its expression, renaming n to n'', and replace the omega argument with error

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1)) // textually replace the x' argument with (n'' - 1)

These are basically mechanical rewrites - replacing function names with their bodies possibly with renaming formal parameters to avoid name collisions, and replacing formal parameters in function definitions with the arguments passed in.

When we consider the expression fact2 0, we evaluate:

fact2 0

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1)) (0)

=> (match 0 with | 0 -> 1| n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (match 0 with | 0 -> 1 (*| n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1)*))

=> 1

Let’s see what happens with fact2 2:

fact2 2

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1)) (2)

=> (match 2 with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (2 * match (2 - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (2 * (* match (2 - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> *) (2 - 1) * match ((2 - 1) - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (2 * 1 * match (1 - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (2 * 1 * match 0 with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (2 * 1 * match 0 with | 0 -> 1 (* | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1)*))

=> (2 * 1 * 1)

=> 2

Now, when we do the same thing with fact2 3, something interesting happens

fact2 3

=> (fun x -> match x with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1)) (3)

=> (match 3 with | 0 -> 1 | n -> n * match (n - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (3 * match (3 - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> n' * match (n' - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (3 * (* match (3 - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n' -> *) (3 - 1) * match ((3 - 1) - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (3 * 2 * match (2 - 1) with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (3 * 2 * match 1 with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> n'' * error(n'' - 1))

=> (3 * 2 * (* match 1 with | 0 -> 1 | n'' -> *) 1 * error(1 - 1))

=> (3 * 2 * 1 * error (0))

=> failwith "0 goes Boom!"

There’s something tantalizing about this approach: one the one hand, we can actually see the composition of the factorial working out nicely, but on the other hand, we have the write fact3 in terms of fact2, and we only get the result when we call the appropriate factN with exactly n otherwise the computation "goes Boom!".

3.3 Please Repeat Yourself!

Let’s consider fact0 0, which as we have seen expands to f (error) 0, and insert the definition of f as an anonymous function. (Note that I have replaced the explicit match expression with the more succinct, but completely equivalent, F# syntax)

The following expression should evaluate to 1

(fun omega ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n -> n * omega(n - 1)

) (error) 0

Let us put a wrapper function around this, which curries in error but takes the anonymous function as its argument. Again, this rewrite is entirely equivalent.

(fun x -> x error)

(fun omega ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n -> n * omega(n - 1)

)

0

What we’ve done here is created a “runner function” which takes a function x and then calls it with error. We then pass in a “workload function” to compute the factorial in as the value of x.

The behaviour before and after the rewrite is identical. Both these functions work for 0 and blow up for 1 just as we expect.

Now, instead of explicitly writing out fact0, fact1, fact2 and so on as before, we could just do repeated invocations of x in the runner function:

(fun x -> x(x(x(x(error)))))

(fun omega ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n -> n * omega(n - 1)

)

3 // succeeds

// 4 // fails

This is actually a kind of cool rewrite. We’re passing in the behaviour we want to be repeatedly performed as an argument to some runner function that does the repetition. That is, we’ve separated out the concerns of doing repetition and computing the factorial into two separate pieces.

Now we observe that factN - or its anonymous equivalent - produces the correct value when it is invoked with N. By seeing how the functions get evaluated, we realize that this is the only way to get to fact0 0, in which case the terminal branch of the match occurs and the error function is not called.

Now all we need to do is to invoke x the correct number of times automatically, and since we’ve separated out concerns, we may only need to do this once for any and all repetitive work we want to do!

Before we figure out how to do that, let’s step back and learn a few more concepts, and then return to this problem!

4 The Lambda Calculus

Because we’ve been working so far with F#, which is a Turing-complete language with recursion primitives, it would seem that it is completely fair to criticise our efforts as unnecessary. Recursion already exists in the language.

So let’s actually learn a tiny little language that has none of these conveniences and get a better sense of the power of this approach. Let’s consider the most foundational of such languages - Lambda Calculus - which has none of the various concepts that traditionally seem inseparably linked to programming and programming languages, such as:

- [❌] Variables

- [❌] Names and Assignment

- [❌] Increment/Decrement

- [❌] Test-and-Branch

- [❌] GOTO

- [❌] Loops

- [❌] Booleans, Integers, Strings or any Types

Anyone who’s starting programming with something close to silicon - say on a microprocessor - would, justifiably, be entirely skeptical that a useful, if not Turing-Complete, language could be possibly be built without any of these primitives.

However, the Lambda Calculus is provably Turing Complete even though it only includes the following two concepts:

- [✅] Function Definition

- [✅] Function Application

Let’s work with just these two concepts and try to synthesize recursion before returning to expressing it in F#.

4.1 Lambda Calculus (The Absolute Shortest Ever Explanation)

The simplest function of all is one that takes an argument and returns it. That’s it.

We write such a function in the lambda calculus as λx.x. In this notation, the λ denotes the definition of an anonymous function, the x (and other symbols) to the left of the . refer to the formal parameters of the function, and the expression to the right of the . is the body of the function. In this example, we take an argument to this anonymous function and return it - the quintessential identity function.

As is immediately obvious, the x really has no implicit significance in the above form - it’s just a symbol. The form λy.y is absolutely identical. So we are free to rewrite any lambda by renaming all occurrences of a symbol with a different symbol that has not been used before. You may run into this in the literature as the α-conversion rule, and it is handy to resolve name collisions when you’re working with a lot of composed forms.

The only other operation afforded to us in lambda calculus is function application, which we represent as just a space-separated sequence of symbols with the function to be applied on the left and the argument to apply the function on to the right.

Like this: (λx.x) b

This is read as “take the function on the left (viz (λx.x)) and apply it to the argument on the right (viz b)”.

To do this, we take the function body and replace all instances of the argument symbol x with the parameter value b, resulting in b, which is what you expect when you apply the identity function on a value b. You may run into this in the literature as the β-reduction rule.

And that’s it. We’re done with Lambda Calculus. All of it.

Going forward, I’m going to skip the formal notation used in mathematical literature and write out actual functions in a weakly typed language in Javascript so we can actually run and evaluate these forms in a browser!

4.2 The Javascript Version

You can generally fire up a Javascript Evaluator in your favourite browser and run the code here in the Console. You can also watch this video for an beautifully detailed explanation of what I’ve summarized here.

Our identity function is simple and elegant: x => x. This is exactly the same expression as λx.x in Javascript syntax.

Applying this function (illegally, because numbers aren’t really allowed in Lambda Calculus) does what is expected: (x => x) (2) // returns 2

Since Lambda Calculus doesn’t have booleans or if-statements, we’re not going to use those constructs from Javascript either. We’re going to build those up from scratch. And since everything in Lambda Calculus is a function, booleans are functions! We’ll define TRUE as a function that takes two arguments and returns the first one, and FALSE as a function that takes two arguments and returns the second.

(t, f) => t) // TRUE

(t, f) => f) // FALSE

Now we can define the NOT function as one that takes a boolean and returns its complement.

b => b(((t, f) => f), ((t, f) => t))

We can see that this gets unwieldy very quickly, so we are going to cheat and allow aliases, noting that we could mechanically replace an alias with its value (with perhaps an α-conversion to resolve name collisions) whenever we wanted to. This leads to a much more tractable approach straightaway:

TRUE = (t, f) => t;

FALSE = (t, f) => f;

NOT = b => b(FALSE, TRUE);

// check

NOT(TRUE)("true", "false"); // evaluates to "false"

NOT(FALSE)("true", "false"); // evaluates to "true"

We can implement other boolean operations and the if-then-else construct

AND = (x, y) => x(y, FALSE);

OR = (x, y) => x(TRUE, y);

IF = (b, x, y) => b(x, y);

//check

IF (AND (TRUE, TRUE), "left", "right"); // evaluates to "left"

I’ll leave it to you to discover how numbers and math operators can be implemented with functions, with the hint that these are called “Church Numerals”.

Once we’ve done all this, we can effectively pretend that we can use numbers, strings, booleans, and if-statements because we have built these up from scratch using nothing but function definition and application - and some entirely mechanical assistance for aliasing and application of rules.

4.3 Looping back to recursion

We still do not have any mechanism for looping or repetitive constructs though. So let’s see how we can implement that using just functions.

Consider a function that takes an argument and applies it on itself. Thus: x => x (x);

Javascript doesn’t complain when we define that function because it is effectively an untyped language in this scenario. And since it’s not actually being applied on anything, the definition is just latently present.

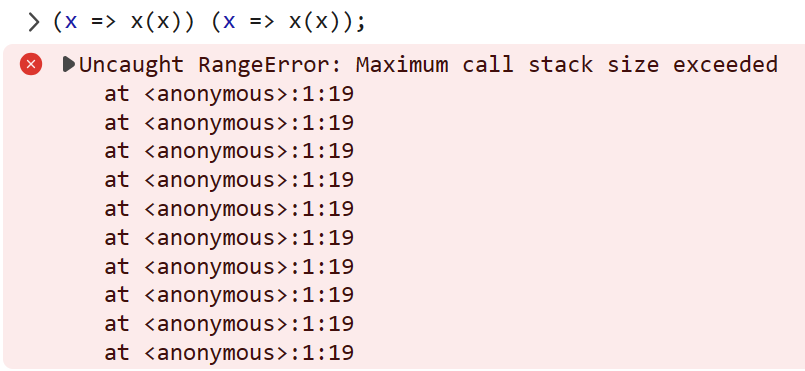

However, something interesting happens if we apply this function on itself, like this: (x => x(x)) (x => x(x));

This immediately evaluates to a stack overflow - indicating that we’re trying to create a kind of infinite “loop” by infinitely recurring!

The reason why this works becomes apparent when we alias it

g = x => x(x);

g (g)

In the first line, we say that g is a function that takes a function x and applies it on itself.

In the second line, we pass in a function that applies itself on itself, to a function that applies itself on itself. If that sounds like a headlong fall into the abyss, it’s because that’s exactly what it is. The function x calls itself by calling itself in a kind of forever evaluation. And this is actually exactly what we were looking for - a kind of infinitely repetitive structure.

This way of synthesizing repetition from nothing more than function application was invented by Haskell Curry, who used this construction to demonstrate a logical construct called Curry’s Paradox. Dive down that rabbit-hole at your own discretion!

4.4 The Fixed Point Generator

Let’s harness the repeated invocation by doing something useful like calling a function f each time. Since we’re not sure what f to use, let’s pass it in as an argument, thus: f => ((x => f(x(x)))(x => f(x(x)))).

Now let’s see what happens when we invoke this function with a function argument g:

(f => ((x => f(x(x)))(x => f(x(x)))))(g) evaluates to the following expression where the formal parameter f in the body of the anonymous function above is replaced with the actual value g:

(x => g(x(x)))(x => g(x(x)))

Now let’s do the same thing again, and apply the right function to the left one - so every x in the left expression is replaced with the right expression. Let us explicitly observe the steps performed mechanically as follows:

- Start with

(x => g(x(x)))(x => g(x(x))) - The left part is a function with one argument

xand bodyg(x(x)). If we pass in a value, sayb, forx, we mechanically replacexwithbin the body of the function, leaving the evaluated valueg(b(b)). - We therefore replace the

xin the body with the function passed in, viz(x => g(x(x))). This results in the valueg ((x => g(x(x))) ((x => g(x(x))))). - We note that the right part of the expression, viz

(x => g(x(x))) (x => g(x(x)))is what we started out with!

That is to say, if we alias the initial expression as Y = f => ((x => f(x(x)))(x => f(x(x)))), then the invocation Y(g) evaluates to g(Y(g))!

Expanding this out a few more times results in the following equivalence chain:

Y(g) = g(Y(g)) = g(g(Y(g))) = g(g(g(Y(g)))) ...

Now this should be somewhat exciting, because when we left the last section we were looking for a way to generate repeated calls to x, and now we seem to have found something that might be able do that!

You’ll come across the term fixed-point in the literature. Y is a fixed-point generator for g in this example.

4.5 Whoa, Nelly!

By looking at this code, we realize that it does almost what we want it do - but it never stops!

The reason it doesn’t stop is because when we ask for Y (g), JavaScript tries to eagerly evaluate all invocations of g at once, and it rapidly descends into the infinite recursion abyss. What we want is for some way to say “Hey, I am going to give you a g - call it only when you need its value”. That way, we can call g sequentially, but we can craft a termination condition into g and get the Y function to stop recurring.

We can do this by wrapping g with a function - which only evaluates g when the wrapper function is evaluated.

More generally, the following rewrite is completely equivalent modulo the delayed evaluation! Given a value or expression x, we can always write it as (n => x)(n). In fact, it doesn’t matter what n is - just that the value of x isn’t evaluated until that wrapper function is called.

Let’s make our Y function lazy thus:

- Take the body of the

Yfunction:f => ((x => f(x(x)))(x => f(x(x)))) - Wrap every

x(x)expression with a suspension function:f => ((x => f(n => x(x)(n)))(x => f(n => x(x)(n)))) - Call this expression

Z, because it’s a lazy version ofYand merits its own name:Z = f => ((x => f(n => x(x)(n)))(x => f(n => x(x)(n))))

Now let’s pass in our familiar function to Z and try to compute the factorial

fact = Z (f => x => x == 0 ? 1 : x * f (x - 1));

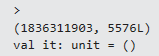

fact (10); // returns 3628800

Hurray! This works!

So we’ve finally hit upon our solution:

- Use a cleverly crafted completely generic expression (thank you, Haskell Curry!) to generate an infinite number of calls in an environment that only supports function definition and application

- Harness the infinitely recurring mechanism to invoke some workload function we want to use repeatedly

- Play some mechanical tricks to introduce lazy evaluation into an eagerly evaluated language

- Terminate the infinite loop at exactly the right time so that the workload function is invoked the correct number of times

Ok, let’s return to the F# world and try the same approach!

5 Curing Schizophrenia

F# is even further removed from the untyped lambda calculus than JavaScript, since it is both eagerly evaluated and strongly typed. This leads us to have to do some type gymnastics to implement what came somewhat more easily in JavaScrupt.

Naively transcribing the Z combinator from above gives us

(fun f ->

(fun x -> f (fun n -> (x x) (n)))

(fun x -> f (fun n -> (x x) (n))))

(fun p ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n ->

n * p(n - 1))

10

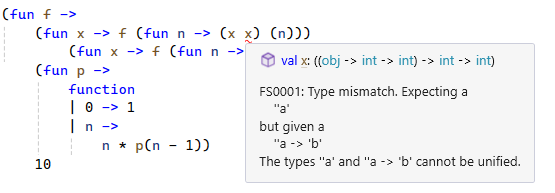

This does not typecheck - and it is instructive to unpack why:

First, let’s see what the compiler complains about with the x in the first expression:

The x parameter is referred to twice in the body - first as a function and then as an argument to that function. Clearly the type system is inadequate to describe this schizophrenic behaviour. What we really want it to do is blindly start recurring, which is what it did in the weakly-typed JavaScript. Roughly speaking, we want x to be a function that takes an object and returns whatever the result of f is.

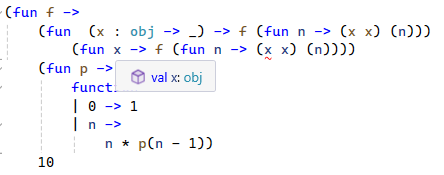

So we can annotate the type with the weaker definition as follows

(fun f ->

(fun (x : obj -> _) -> f (fun n -> (x x) (n)))

(fun x -> f (fun n -> (x x) (n))))

(fun p ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n ->

n * p(n - 1))

10

This has the desired effect and the compiler accepts the first expression as valid. This forces the type inference of the second lambda to take an argument of type obj.

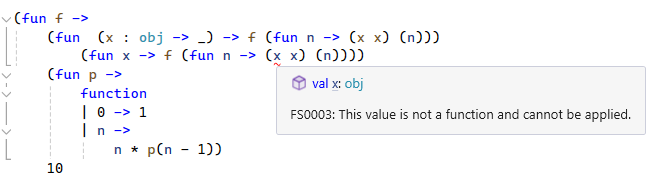

Of course, this then completely confuses the F# compiler, because we go ahead and apply the value x as a function in the body of the second lambda. So the compiler complains saying that it can’t apply an object like a function.

In reality, because the only object type in lambda calculus is the function type, x is both an obj and a function, so we have to encode this schizophrenic behaviour as type annotations.

(fun f ->

(fun (x : obj -> _) -> f (fun n -> x x n))

(fun x -> f (fun n -> (x :?> obj -> _) x n)))

(fun p ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n ->

n * p(n - 1))

10

// 3628800

We agree with the type-checker that the parameter x to the second expression is an object, and then arm-twist it to treat it like a function when we need to apply it. We can do this because we know that it’s really a function and we’re only disguising it as an object to get around strong typing.

This now runs just fine, and we’ve successfully synthesized recursion using just function application some type gymnastics. Just like we did in JavaScript, we can christen the Z combinator.

let Z f =

(fun (x : obj -> _) -> f (fun n -> x x n))

(fun x -> f (fun n -> (x :?> obj -> _) x n))

To my eyes, this is only a tiny bit less elegant than the JavaScript version!

Z = f => (x => f(n => x(x)(n))) (x => f(n => x(x)(n)))

6 Lifting Heavy Things…

We’ve worked through a lot of concepts to get to this point. We’ve had to try to synthesize recursion by building up repetition manually, grok Lambda Calculus, play with JavaScript and encounter the Y and Z combinators, and then do type-gymnastics to transliterate the solution to F#.

Was there a point to all of this? After all, F# and JavaScript both have native support for recursion, so this does feel like a lot of activity with a useless, albeit academically curious, resolution.

Or is it?

6.1 Logging and Tracing

Let’s go back to the factorial generator function:

let fact_gen =

(fun p ->

function

| 0 -> 1

| n ->

n * p(n - 1))

Now we know that the fixed point of this function is the fact function which computes the factorial of a number.

let fact = Z fact_gen

fact 10 // 3628800

Now, let’s say we want to actually log each invocation of fact_gen, but without having to modify the fact_gen code itself. This is a reasonable requirement, as we have gone through some effort to separate out the concern of computing a factorial term from everything else, and we don’t want to start mixing other concerns like logging into it!

Now, one observation we made when we derived the combinator was that the g we passed into Z g was invoked once per “iteration”. Now we want to do two things per iteration - log that iteration happened, and compute the factorial term. As functional programmers, we have a favourite tool for this kind of thing: function composition, so let’s use it:

let log (f : 'a -> 'b) =

(fun x ->

let result = f x // invoke the function we're logging...

printfn "%A -> %A" x result // ...and log the argument and result

result)

let fact_with_log = Z (fact_gen >> log)

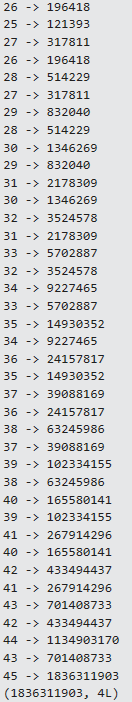

fact_with_log 13

which prints out

6.2 Memoization

Let’s really take advantage of the fact that we get control on every recursion stage now.

Memoization is a powerful technique to trade off space for compute time, providing an elegant way to reduce recomputation. We can write a naive memoize function for a function of one argument like this:

let memoize (map : System.Collections.ConcurrentConcurrentDictionary<'a, 'b>) (f : 'a -> 'b) =

(fun x -> map.GetOrAdd(x, f))

let m

We could use this with a simple function as follows:

let square x = x * x

let square x = x * x

let sqm = memoize (new System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary<_,_ > ()) (log square)

sqm 3 |> printfn "%A";

sqm 3 |> printfn "%A";

sqm 3 |> printfn "%A";

which results in

Clearly showing that that the actual square method was called once, and the next invocations just found and returned the result from the cache.

Why is this naive? Well if we tried to use this on a recursive function, memoize would only be able to wrap the outermost call - and the inner recursive calls would still be executed repeatedly.

Let’s see this in action:

let rec fib =

function

| 0 -> 1

| 1 -> 1

| n -> fib (n-1) + fib (n-2)

let time (f : unit -> 'a) =

let timer = new System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch()

timer.Start()

let result = f()

timer.Stop()

(result, timer.ElapsedMilliseconds)

time (fun () -> fib 45) |> printfn "%A"

This eventually finishes in about 5.5s

Contrary to most expectations, memoizing this function will not improve anything:

time (fun () -> (memoize (new System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary<_,_ > ()) (log fib)) 45) |> printfn "%A"

We note that the log method is only called once, and the time is roughly the same.

Of course, we can see why immediately - it’s because the recursive calls in the body of fib have not been memoized, and indeed we have no way of doing that without rewriting the innards of the fib function.

However, if we recognize that the fixed-point combinator gives us control over each recursive invocation, allowing us to intercept the call and either update or access the cache, then it becomes possible to gain the benefits of memoization very elegantly.

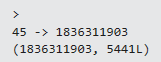

For this, we extract the fib computation from the in-built F# recursion mechanism, and memoize that:

let fib_gen fib =

function

| 0 -> 1

| 1 -> 1

| n -> fib (n-1) + fib (n-2)

let fib = Z (fib_gen >> (memoize (new System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary<_, _>())) >> log)

time (fun () -> fib 45) |> printfn "%A"

And there we have it - each call to compute fib happens only once, as is evidenced by the log - and the whole computation takes 4ms instead of a thousand times longer.

This is actually a real-world example of where we would need to understand and use fix-point combinators, because they give us a much more flexible and controlled mechanism to do recursion - and this kind of control is what makes all the effort we put in worth it - even though languages like F# and JavaScript have in-built recursion.

Are there any other applications that come to mind as you read this?

7. Conclusion

We’ve finally reached both a deeper understanding of the functional foundations of recursion, and seen some of the power of what it affords.

- We started with continuations and separated out the mechanism for invocation from the workload being invoked.

- Then we switched to an untyped language and encoded a few primitives of lambda calculus, showing how we could derive all the familiar things we were taught as primitive from just function definition and application

- We then borrowed an idea from Haskell Curry and came up with a scheme of function application that goes on forever,

- We then crafted a way to inject the workload function into this scheme so we could do repeated invocation. This resulted in the

Ycombinator - Then, because we started with a language that did eager evaluation, we found a way to suspend computations so we could terminate the invocation sequence based on the workload. This resulted in the

Zcombinator - Then we took that scheme and got it to work in a strongly-typed language like F#.

- Finally, we saw some examples that used the fact that we had much more control over the recursion using the

Zcombinator to do something we couldn’t do with the language-provided recursion mechanisms.

I hope this rather lengthy document was lucid and effective in its explanation of the Y (and Z) combinators as Jim’s talk was. Again, we - as a community - continue to be indebted to his work and contributions.

I also hope that this gave you a flavour of how powerful and useful recursion can be.

In fact, the point has been made, and cogently, that the entire branch of dynamic programming which seeks to obviate recomputation by cleverly refactoring the problem to be solved can be profoundly impacted by using memoization - which achieves the same goal without sacrificing a (usually succinct) top-down description of the problem.

But that is a discussion for another day, and this is a good place to stop.

Happy Holidays!